The prospects of a trilateral summit between South Korea, China and Japan, potentially to be held by the end of May, are looking rather uncertain as geopolitical tensions show no signs of abating especially between Beijing and Seoul.

Analysts ponder whether the summit, if held, will produce any meaningful results, while calling for a much-needed channel for communication between the major East Asian economies.

“From the current international geopolitical situation, the environment for a trilateral summit between China, Japan and South Korea is unfavorable — one might even say dire,” said He Jun, a senior analyst with Anbound, a Beijing-based public policy think tank.

The current relationship between China and South Korea is at its lowest point since the establishment of diplomatic ties in 1992, he added.

The comments came as South Korea has been actively signaling its intent to revitalize the meeting. Still, China has been unhappy with Seoul’s increasingly outspoken remarks about the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea, as well as its expanding security and economic ties with the U.S. and efforts to diversify its economy away from China.

“However, even amid adversity, a trilateral summit between the leaders remains necessary. Dialogue is better than no dialogue,” he said, adding that China will not hold the summit in high regard, but that the significance lies in the contact itself between leaders from the three East Asian powers.

The three countries are in talks to hold a long-overdue high-level summit likely on May 26 or 27, according to a report by Japanese daily Yomiuri Shimbun last week.

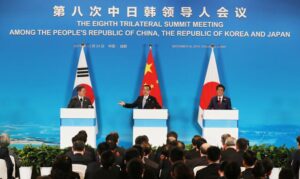

The summit has been suspended since December 2019 when then-Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, then-South Korean President Moon Jae-in and then-Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe met in the Chinese city of Chengdu.

As the host, the conservative President Yoon Suk Yeol is actively pushing for the high-level meeting, especially after experiencing a massive political setback in the general elections last week.

“It would be an opportunity for Yoon to be able to showcase his diplomatic achievements, offsetting the parliamentary election losses, but China will have to see his attitude,” said Zhang Huizhi, a professor of Northeast Asian studies at Jilin University in China’s northeastern Jilin province.

However, his actions, such as Seoul’s cooperation with the U.S. in restricting semiconductor-related exports to China and contemplating joining AUKUS, have strained relations further, deepening Beijing’s dissatisfaction.

“If there’s a new stance from Yoon recently, it might help push things forward,” Zhang added.

When asked about the trilateral summit, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs gave ambiguous comments that signaled a degree of uncertainty.

“The Chinese side attaches importance to cooperation among China, Japan and South Korea. We hope that the three parties can jointly create conditions for holding a leaders’ summit,” ministry spokesperson Mao Ning said last week.

“We are also willing to maintain communication with South Korea and Japan on the preparation for the leaders’ meeting.”

The subtle hints in the response indicate that an agreement has yet to be reached regarding the agenda for the meeting, according to Kang Jun-young, a Chinese studies professor at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Seoul.

While South Korea may seek China’s assistance in containing military threats from North Korea and addressing the North Korean nuclear issue, China does not seem inclined to discuss this topic, which is perceived as a matter between South Korea and the U.S., Kang said.

But before dealing with the nuclear issues, the two countries should re-establish an atmosphere of communication between themselves as well as their people. The relationship has been quite rocky following the deployment of a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system in 2016 on South Korean soil.

“It’s natural for problems to arise, but when they do, how can they be addressed? A resolution mechanism has been absent for over three decades — this is the biggest issue between South Korea and China,” Kang said, adding that both or all three countries should understand each other’s issues and what can be done under the current framework.

Kang said that many Chinese local governments are keen to work with South Korea, but are held back by the general atmosphere. If local-level exchanges can continue, new starting points could emerge to organically catalyze business exchanges, he said.

“This summit would mark the first gathering since the pandemic. Given the changing international landscape and supply chain dynamics, these three nations need to find better development directions,” Kang said. “Topics such as industry and the economy are up for discussion while this summit should be used as an opportunity to chart a new course.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping is unlikely to attend the meeting; instead, Prime Minister Li Qiang may participate, which could be interpreted as “a subtle gesture of China’s discontent with the other two countries’ strengthening ties with the U.S. in the past few years,” said Xue Fei, senior analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit.

“We expect the upcoming trilateral high-level meeting to focus on maintaining peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region, efforts to contain trade frictions and overcapacity in certain industries such as clean energy and electric vehicles, the strategic weapons program and weapons testing by North Korea, among others.”

Meanwhile, China will also caution against the establishment of alliances in the region that target specific countries, he added.

Compared with its neighbors, Japan is the least invested in the meeting, experts pointed out.

“From Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s current focus and concerns, the trilateral summit is not something he prioritizes, and he is unlikely to make any serious efforts to promote it,” Anbound’s He said. ( Source: Korea Times)