ISLAMABAD ( WNAM REPORT ): In Pakistan’s bustling online marketplace, a shadow economy is thriving. From Facebook pages openly selling untaxed cigarettes to WhatsApp groups coordinating the sale of smuggled fuel, social media platforms are becoming powerful enablers of illegal trade. Experts warn that this growing digital black market is costing the country trillions of rupees in lost tax revenue and threatens Pakistan’s already fragile economy.

According to recent estimates by PRIME, an Islamabad-based think tank on economy, Pakistan loses approximately Rs. 3.4 trillion annually to smuggling, tax evasion, and counterfeit goods—equivalent to over 3.5% of its GDP. These losses represent nearly a quarter of the government’s total tax collection targets and significantly weaken its ability to fund public services, repay debt, and invest in development.

Mubashir Akram, Country Director of ACT Alliance Pakistan, paints a grim picture. “This is not just about lost revenue—it is about our economic future. Illegal trade has hollowed out entire sectors of the economy. If we are serious about achieving economic independence, we must dismantle these illegal networks and bring those involved to justice.”

Cigarettes, Fuel, and Tea: A Trillion-Rupee Black Hole

Illegal trade is particularly rampant in the tobacco sector, where over 56% of Pakistan’s cigarette market is now dominated by illegal brands. These brands bypass government taxation entirely, leading to annual losses estimated between Rs. 300 to 400 billion. The legal industry, despite being fully compliant and contributing nearly Rs. 300 billion in taxes annually, is steadily losing market share to these underground operators who sell cheaper, untaxed products.

Fuel smuggling is another major concern. Diesel and petrol from Iran—where prices are significantly lower—are brought across the porous border into Pakistan and sold at reduced rates through informal networks, often coordinated on social media. It is estimated that 30–35% of diesel consumed in Pakistan may be illegal, costing the exchequer another Rs. 225–270 billion every year.

Meanwhile, smuggled tea, beverages, pharmaceuticals, and electronics add to the fiscal damage. Tea smuggling alone results in losses of billions in customs duties and taxes annually. In the pharmaceutical sector, counterfeit and illegally imported medicines—sold widely through Facebook and Telegram—pose both financial and public health risks.

“These are not small-scale backdoor operations anymore,” Akram warns. “We are talking about organized, technology-enabled networks that are operating in plain sight on digital platforms. And they are getting bolder.”

Social Media: A New Marketplace for Illegal Trade

Platforms like Facebook, TikTok, and WhatsApp have become hotbeds for marketing and distributing smuggled goods. Sellers post photos of untaxed cigarettes, smuggled perfumes, foreign medicines, and even barrels of diesel, often with contact details or links to encrypted messaging groups. These platforms allow sellers to reach consumers across Pakistan, avoid scrutiny, and operate without the fixed footprint that law enforcement agencies can easily target.

Closed WhatsApp groups are now being used to coordinate large-scale deliveries of illegal POL products and non-duty-paid cigarettes to fuel stations and retail outlets. TikTok has seen a rise in influencers discreetly advertising counterfeit branded goods—ranging from watches to supplements—without disclosing their illegal nature.

“The unchecked use of social media for illegal commerce is a major challenge,” says a senior FBR official. “These platforms are borderless, fast-moving, and difficult to regulate under our current legal framework.”

The Routes of Smuggling: Afghanistan, Iran, and Beyond

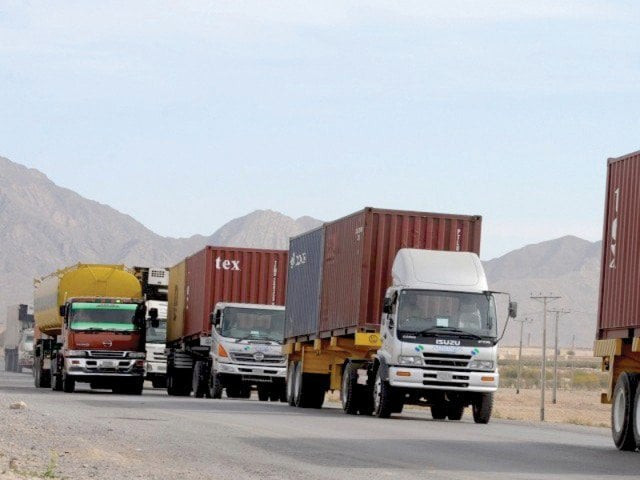

Much of Pakistan’s illegal trade flows through its long and porous borders with Afghanistan and Iran. The Afghan Transit Trade (ATT), originally intended to supply duty-free goods to Afghanistan, is often misused. Containers meant for Afghan markets are diverted within Pakistan, flooding local bazaars with electronics, fabrics, tyres, and consumer goods without paying duties. This abuse alone is believed to contribute to more than Rs. 1 trillion in annual revenue losses.

From the western border, fuel smuggling from Iran has grown into a multimillion-dollar industry. Thousands of liters of subsidized Iranian petrol and diesel are brought into Balochistan daily, often through pickup trucks or motorcycles. According to petroleum dealers, smuggled fuel now accounts for up to 40% of retail diesel sales in some cities, severely damaging local refineries and licensed distributors.

Despite occasional raids, smuggling continues unabated due to challenging terrain, limited enforcement capacity, and local complicity. Videos of fuel being transported in broad daylight—shared ironically on social media—highlight just how normalized the problem has become.

Undermining the Economy, Destroying Trust

The economic consequences are profound. Trillions in lost revenue weaken the state’s ability to fund education, health, infrastructure, and social safety nets. For an economy reliant on external debt and IMF bailouts, plugging these leakages could reduce the need for austerity and restore some fiscal sovereignty.

Equally concerning is the impact on fair competition. Legitimate businesses operating within the tax net are consistently undercut by illegal operators who can offer lower prices by evading taxes and regulations. This not only stunts job creation and innovation but erodes investor confidence—both local and foreign.

“Every rupee lost to tax evasion is a rupee not spent on schools, hospitals, or clean water,” says Akram. “And every day we let this continue, we send the message that law-abiding businesses do not matter.”

Enforcement Steps: A Glimmer of Progress

In recent months, the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR), the Inland Revenue Enforcement Network (IREN), and the Pakistan Customs have launched a series of operations targeting smuggled goods. Raids in Karachi, Quetta, and Peshawar have resulted in the seizure of illegal cigarettes, fuel, tea, and luxury items worth billions.

The government has also introduced digital tracking systems—such as track-and-trace stamps for cigarettes—to monitor legal supply chains. However, implementation remains patchy, with compliance still limited to a fraction of brands.

The FBR has recently approved the hiring of 100+ sector specialists to strengthen audit and enforcement across 42 high-risk industries, including tobacco, POL, real estate, and textiles. These steps, while encouraging, must be scaled and sustained.

The Road Ahead: Economic Independence through Rule of Law

Pakistan’s challenge now is to ensure that recent momentum is not lost. For Akram, the answer lies in institutional continuity and political resolve.

“We achieved political independence in 1947, but economic independence remains elusive. If we are to break the cycle of debt and dependence, we must reclaim what is ours—our revenue, our markets, and our rule of law.”

He concludes with a message that resonates widely among Pakistan’s struggling formal businesses: “The government must stay the course. Enforcement cannot be seasonal. The mafias involved in illegal trade do not take breaks—and neither should the state.”