In the contemporary world of international relations, the “region-to-region” cooperation format is gaining increasing popularity. Current challenges in the areas of security, sustainable economic development, and social stability require not only the active involvement of nation-states and individual regions but also the advancement of interregional cooperation. This format facilitates the edmergence of new trends in the international arena and contributes to the strengthening of multi-level partnerships.

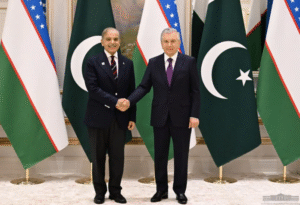

One of the most prominent examples of such cooperation is the dialogue between Central and South Asia, which is becoming a significant trend within the broader Eurasian context. The international conference “Central and South Asia: Regional Connectivity. Challenges and Opportunities,” held in Tashkent in July 2021, served as a starting point, giving impetus to the development of interregional cooperation. The upcoming Termez Dialogue, scheduled for May of this year, promises to mark a new stage in this process. Within the framework of this dialogue, Uzbekistan and Pakistan are expected to play a pivotal role, being regarded as key actors capable of shaping the trajectory of further rapprochement and coordination between the two regions.

Why Uzbekistan and Pakistan?

The interregional cooperation format of “Central – South Asia” has attracted the interest of many major global powers. Originally, the initiative was promoted by the United States as a tool for enhancing regional connectivity. However, following the U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, Washington’s engagement in promoting this format has notably diminished.

Currently, China and Russia are showing significant interest in the initiative, viewing it as a potential instrument for expanding their influence across Eurasia. Nevertheless, their involvement remains largely political and declarative, lacking concrete financial commitments and well-defined projects under the “region-to-region” cooperation framework. India and Iran also support the idea of regional interaction but prioritize maritime transport routes – such as the port hubs of Chabahar and Mumbai – which they perceive as more promising for connectivity than land corridors traversing Afghanistan.

In contrast, Uzbekistan and Pakistan have demonstrated the most tangible interest and practical engagement in developing the “Central – South Asia” cooperation format. These two countries have emerged as key beneficiaries of this initiative, advancing economic and transport projects backed by concrete investments and institutional efforts. In the long term, the depth of their engagement, their political will, and their financial commitment will be decisive in shaping the dynamics and effectiveness of interregional cooperation within the “region-to-region” paradigm.

The Priority of Geoeconomic Interests

At the current stage, Uzbekistan and Pakistan are demonstrating a notable shift in their foreign policy strategies from geopolitical priorities to geoeconomic ones. Uzbekistan is pursuing a pragmatic and multi-vector foreign policy, aiming for active participation in major infrastructure and logistics initiatives spanning the Eurasian continent. Key projects in which the country is involved include the Middle Corridor, the Belt and Road Initiative, the North-South International Transport Corridor, and the Trans-Afghan Corridor.

In this context, South Asia assumes particular importance for Uzbekistan, which views the region – especially countries such as Afghanistan and Pakistan – as a promising export market within a broader regional framework. Furthermore, access to maritime ports via Afghan and Pakistani territory is of strategic significance for Uzbekistan, a landlocked state. The implementation of such projects not only facilitates the country’s integration into global economic supply chains but also transforms its territory into a crucial transit hub for other Central Asian nations and the Russian Federation.

Pakistan, for its part, also prioritizes geoeconomic interests. One of the core components of its foreign economic policy remains its involvement in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, particularly through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Additionally, Islamabad seeks to deepen cooperation with the Russian Federation, particularly in the agricultural sector – Russia has become one of Pakistan’s main wheat suppliers. Pakistan views Central Asia as both a new market and a potential transit route to northern Eurasia.

Thus, Uzbekistan and Pakistan exhibit convergence in their external economic approaches, placing a shared emphasis on the development of connectivity, infrastructure, and market access. Both countries pursue multi-vector policies aimed at enhancing their roles in Eurasian integration and transit projects. This commonality strengthens their strategic importance within the framework of “Central – South Asia” cooperation.

The Afghanistan Factor

The Afghan issue represents a key dimension of cooperation between Uzbekistan and Pakistan. Both countries, as Afghanistan’s immediate neighbors and economic partners, play a significant role in supporting its socio-economic development, including the provision of humanitarian assistance. Given Afghanistan’s current state of international isolation and exposure to sanctions, the country is particularly reliant on the support of its neighboring states.

Despite the Taliban having held power for over three years, their government has yet to receive international recognition, and Afghanistan’s external financial assets remain frozen. Nonetheless, efforts have been made within the country to promote recovery and modernization: initiatives to combat opium poppy cultivation and corruption have been launched, a tax system is being implemented, qualified professionals are gradually returning to administrative roles, and attention is being paid to the development of education.

In this context, Uzbekistan and Pakistan have emerged as active advocates of Afghanistan’s sustainable development. A key infrastructure initiative is the construction of the Trans-Afghan Transport Corridor. Since 2023, a project office in Tashkent has been coordinating the implementation of this route. For Uzbekistan, the corridor provides access to Pakistani ports such as Karachi and Gwadar, while for Pakistan, it offers a gateway to the Central Asian market. Afghanistan, in turn, plays a critical role as a transit hub within this project.

The development of education and human capital must also become a strategic priority. Both countries have already taken concrete steps in this direction, for example, Uzbekistan is constructing a madrasa in Mazar-i-Sharif for 1,000 students. Such initiatives should be expanded further, including through scholarship programs and educational opportunities for Afghan students. These measures will not only contribute to the socio-economic stabilization of Afghanistan but also foster stronger ties among the peoples of the region.

Challenges

Despite ongoing efforts to restore historical ties among the countries of the region, several challenges continue to hinder deeper cooperation.

First, there is a notable deficit in public diplomacy mechanisms. Relations among Uzbekistan, Pakistan, and Afghanistan largely remain confined to the intergovernmental level, with few joint educational or cultural initiatives. Notably, there are no shared universities among these states, which limits academic and youth exchanges. This shortfall restricts opportunities for young people and students to study the languages, cultures, and societal dynamics of neighboring countries. Additionally, there are no dedicated information centers to foster mutual understanding, which affects the level of cooperation between journalistic and expert communities.

Second, transportation connectivity between the countries remains weak. Air travel is limited to a small number of flights, particularly those connecting Tashkent with Kabul and Lahore. The Trans-Afghan Transport Corridor, which is expected to enhance regional logistics, is still under construction. At present, trade and mobility largely depend on highways, which restrict both the volume of trade and the movement of people.

Third, unresolved issues concerning the joint use of transboundary water resources persist. Uzbekistan and Afghanistan continue to engage on the equitable distribution of the Amu Darya River’s waters, particularly within the context of Afghanistan’s Kush Tepa Canal project. At the same time, disagreements between Pakistan and Afghanistan remain over the use of the Kunar River, where Afghanistan is constructing a hydroelectric power plant. While both Uzbekistan and Pakistan support Afghanistan’s aspirations to develop its agricultural and energy sectors, they also emphasize the importance of adhering to international environmental and water-use standards.

Fourth, radicalism and extremism remain serious regional threats. The presence of extremist groups in Afghanistan, such as ISIS-Khorasan and Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), raises significant concerns and necessitates coordinated counterterrorism measures. Platforms such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Termez Dialogue can play a vital role in building a comprehensive approach to regional security.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In the context of growing interdependence and the dynamic nature of global processes, cooperation between Central and South Asia is gaining particular relevance. This format holds the potential to become a model for “region-to-region” engagement, contributing to sustainable development, security, and mutually beneficial integration. However, the full realization of this interregional cooperation requires the institutionalization of relations.

- One promising platform in this direction is the Termez Dialogue, which could function as a multi-level forum for both political and expert-level discussions on key issues of cooperation. This format should not be limited to state actors but should also include representatives from academic and business communities, facilitating the development of practical solutions. To deepen and expand interregional cooperation, it would be advisable to initiate complementary dialogues in Peshawar and Kabul, modeled after the Termez Dialogue. Such initiatives would help decentralize communication and engage a broader range of stakeholders, representing a significant step toward establishing resilient interregional institutions capable of coordinating projects in transport, energy, education, and security.

- To advance public diplomacy, humanitarian ties, and educational exchange, it is recommended to expand international scholarship programs, particularly in priority fields such as education, engineering, medicine, and scientific research. Such efforts would enhance mutual understanding among nations and help cultivate the human capital necessary for implementing joint projects.

- A particularly relevant initiative could be the establishment of a Central and South Asian Joint University in Termez, envisioned as an academic hub uniting students, educators, and researchers from countries across both regions. The proposed university in Termez could evolve into a center of educational cooperation, a platform for transboundary scientific research, and a catalyst for innovation projects contributing to the region’s sustainable development.

- In addition, the establishment of a Museum of the Peoples of South and Central Asia in Lahore would promote cultural rapprochement, preserve historical heritage, and advance the idea of regional unity. The museum could host exhibitions, conferences, and cultural programs aimed at fostering mutual respect and interest among the societies of the region.

In conclusion, the formation of institutional mechanisms, the enhancement of humanitarian ties, and the strengthening of educational cooperation are essential for transforming Central-South Asian engagement into a sustainable and replicable model of interregional partnership.

The author is : PhD in Political Science, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Afghanistan and South Asian Studies, Institute for Advanced International Studies, University of World Economy and Diplomacy

Tashkent, Uzbekistan.